https://instagram.com/p/BnCsKIWgVj_/ |

Farm and garden productivity and profitability

Reduced irrigation requirements

Reduce cost of fencing and livestock management and feeding

Home and garden security

Improved livability and reduced home heating and cooling costs

Reduced pest and disease pressures

Increased pollinators, native flora and fauna,

Increased soil health and fertility,

Increased water health,

Increased biodiversity and overal ecosystem health

Fight climate change by sequestering a whole lot of carbon

And provide more food for less work than just about any thing else you can do?

Then here's your word for the day: "hedgerows."

(Schematic for a typical hedgerow in Normandy, France.)

Hedgerows, or living fences and boundaries have been planted by humans for at least 6,000 years (Mueller, European Field Boundaries) to cheaply and easily provide a long, long list of services and simplify landscape management.

Across climates, including in the tropics most researchers are stressing the importance of these "anthropogenic" systems to the health of ecosystems, with research domonstrating their value to wildlife, their ability to increase biodiversity, bolster native bird and invertebrate populations, act as a buffer from agricultural pollution, clean water, recharge aquifers, mitigate soil loss and erosion, sequester carbon, and so on.

Across Europe and Asia, in cultures where hedgerows were common landscape feature , they are now being recognized for their value, and cherished for their associated cultural traditions and character within the landscape. In many countries, such as the UK or Japan, they are associated with culinary traditions, are considered an important part of the sense of place, such as the "bocage" landscapes of France, or have long-standing spiritual symbolism or religious and cultural traditions associated with them.

Even in North America, where we culturally lack the deep appreciation for hedgerows, bocage, and "mosaic landscapes," and environmentalism is more influenced by the mythology and assumptions about a wide-open American "wilderness" untouched by humans (despite the large native population), Universities widely reinforce the high value of hedgerows and windbreaks for ecosystem health and agricultural productivity, and decry the loss of these features due to poor economic choices and poor understanding of food safety practices, as a tragedy.

And while some agricultural authorities working under Food Safety and Modernization Act regulations superstitiously eye hedgerows with suspicion (or suggest that removing some hedgerows might be a "balanced approach) research continues to show that hedgerows do NOT pose a risk for contaminating food, and actually reduce risk while removal and "mitigation" efforts such as tilling around hedgerows may actually increase risk.

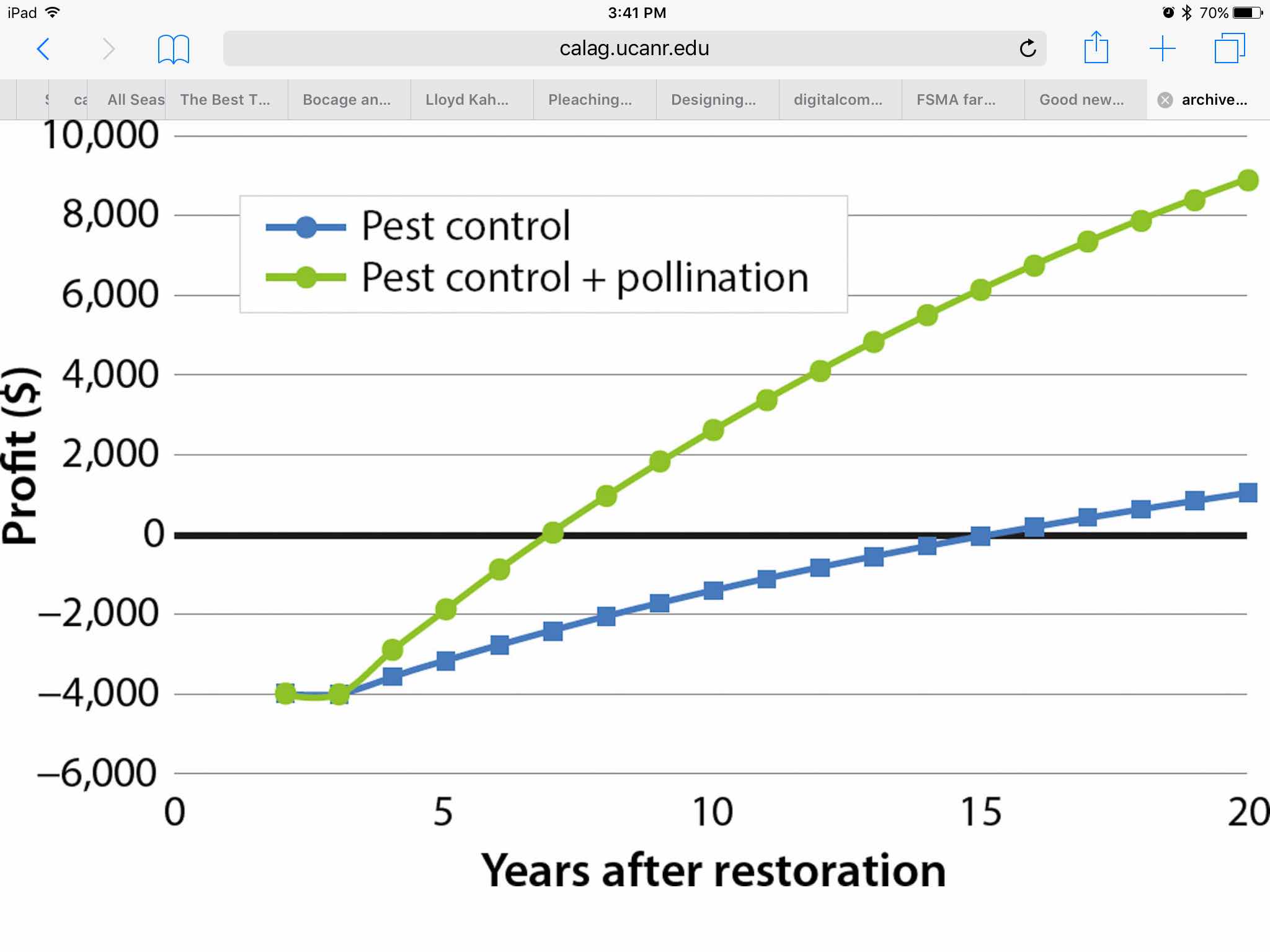

But many studies have show that the improvements to ecosystem health from restoring hedgerows do carry benefits to humans in farming, gardening, home or other productive landscapes, including reduction in pests, and increase in pollination.

In addition to a positive effect ecosystems, hedgerows can have more direct benefits and yields to humans depending upon their design, including firewood, building materials, reduced irrigation, increase soil fertility, free fertilizer, improved soil carbon, reduced soil loss, garden stakes and trellises, tool handles, better plant growth from shelter, and of course, foods and medicines. In most places where hedgerows exist, they have long been seen as an important source of both.

Designing an Edible Hedgerow or Tapestry Hedge

While one can use similar techniques for broad-scale windbreaks or livestock enclosures by making appropriate adaptations, this article will focuss on the small-scale edible hedgerow or tapestry hedge, based off of European designs and traditions.

It was a couple of our favorite foraging spots which inspired our desire to have an edible fence. One in particular, was a naturally-occuring hedgerow that produced a large variety and quantity of fruits, nuts and vegetables throughout the season, all with little to no annual maintenance from humans.

Compared to our hard work as guest farm laborers, the high rewards and low maintenance of our favorite hedgerow seemed like a great idea, and we decided to "take it home" with us.

But when we began looking into expert recommendations on how to grow an edible hedge in the US, we were surprised to see everyone advocating against the species and spacings that was common to our favorite foraging spots.

Was mother nature growing these natural food forests all wrong, as the experts suggested?

Traditional Spacings: Tight!

However, when we looked into resources on traditional hedge culture, species and techniques in other countries, we found systems that looked very much like what was occuring naturally at our favorite high-productivity, low-maintenance spots. (Mueller, European Field Boundaries Volumes 1 &2, etc.)

While modern US recommendations look very different in terms of species selection, and management, the biggest difference between traditional hedge, hedgerow and windbreak technologies, and modern recommendations (at least in the US) is in spacings. Most common recommendations I can find from US sources recommend planting at spacings where crowns just intermix or touch at maturity (perhaps 7-10' centers for many shrub species, with many suggesting 5' was too tight) whereas traditional forms typically space plants at 1- 2 1/2'.

While these seem very close to a gardener, these spacings approximate what one commonly sees occuring in natural thickets in many biomes, including our favorite foraging locations.

But, despite the expert recommendations, these tight naturalistic plantings found in traditional hedgery, which have proven their effectiveness in experiments over millennia, have become the cutting edge of scientific forestry (as well as many Permaculture circles) throughout the world, since the 1980s when a Japanese forester named Akira Miyawaki took notice of the way Nature grows forests.

It's no coincidence that this evolved technology of hedgerows closely resembles the cutting edge reforestation program referred to as the Miyawaki technique. Miyawaki was a forester interested in regrowing healthy forests in Japan for purpose of maintaining habitat, controlling erosion, sequestering carbon and solving other problems through the ecosystem services, who noticed that the plant spacings and communities used in "conventional" forestry practice looked nothing at all like the types of spacings and communities that would occur during natural reforestation, and that the conventional approach often performed poorly in comparison to the way nature solved this same problem. He hypothesized that the conventional recommendations were tested and developed to optimize commercial yield in various ways, not to optimize fast, easy cost-effective establishment of healthy forest. Basing his approach off of the observation of naturally-occuring rapid reforestation, he developed a system of using seed from locally-adapted, free specimens, with intermixed stages of succession, at very tight plantings, and he found that nature was solving the problem the right way. Across many climates and ecosystem types, Miyawaki's technique has been replicated and found to far out-perform conventional practice, with far less cost and fewer destructive chemical inputs.

Indeed, some US sources appear to criticize Miyawaki's methods as inappropriate to North America's idealized "natural landscapes," because they do not leave enough room for our most important North American "nature area" keystone species: tax dollars, corporate petrochemicals, herbicides, and heavy machinery.

For some, it's counter-intuitive, but research has found that even on spare soils in dry climates with a risk of desertification, the tight plantings of the Miyawaki technique lead to rapid establishment with little after-planting care, even where conventional techniques failed with continued Intervention!

This goes well with current ecological theory and research, which has found that while we previously believed that competition between plants would impair growth and establishment, in such tight, naturalistic plantings cooperation out-weighs competition and gives the individuals an advantage compared to situations with unnaturally wide plant spacings.

(Integrated Hedgerow design by Bill Mollison, for Semi-tropical climate)

Moreover, with rapid, dense growth, we humans can begin to reap the rewards of ecosystem services - windbreak, enhanced microclimates, erosion-prevention, water harvest, buffering, wildlife habitat, biodiversity and food (under tight plantings most species will bare "precociously" at an early age) - in a very short order, rather than struggling with establishment for 15 years for a wind-break to finally serve its purpose. With all this, it's no wonder that cutting-edge Permaculture designers like Geoff Lawton have begun to implement Miyawki's research for such applications as forest gardens, ally cropping and, of course, hedgerows.

As a very rough guideline, my recommendation for a hedge where production is the main goal is to plant into a 10' wide strip of at least 30' of length (to have much room for diversity) with larger woody perennials at 2'-3', and with smaller woody shrubs and herbaceous perennials filling in the gaps to create approximately 1' spacings. I typically don't plant anything direcly between woody perennials, except perhaps for short-term crops like Jerusalem artichokes, which can provide a big yield in early years, ensure a complete hedge effect in the first season, provide ample biomass for mulch, and then die back as woody perennials establish. For best results, very plants by height, and species, planting main species such as hazelnuts at standard spacings, and filling in the gaps with smaller species. For larger hedgerows and windbreaks, I recommend multiple rows of woody perennials, but still at tight plantings. For hedges where security or animal enclosure is the main goal, I recommend 1' spacings, with a high percentage of thorny species such as hawthorn, blackthorn, or sea buckthorn.

Permaculture Design Parameters:

With hedgerows being so useful, it's no wonder that many of Mollison's early designs included hedges, shelterbelts, sun-traps and windbreaks. Permaculture 2 is filled with whole sections on these features.

In addition to siting the hedgerow to provide as many benefits as possible, one should consider mechanisms to insure adequate water and appropriate drainage. Hedgerows are excellent features on swales or micro-swales. Net and pan design can be used to make watering easy and help plantings be self-watering. We used a system of net and pan along with trench composing swales to make sure that water would flow down our hedgerow, providing adequate water to our young trees during establishment while also keeping water from completely filling planting holes on our very compacted soils with extremely poor drainage. This can be seen in some of the establishment shots in our Hedgerow video. Integration with keyhole gardens and "edible border gardens" are an excellent idea, and common in the English and French gardening traditions.

Species selection for Temperate regions

For our main woody perennials, we'll need plants that share a few major charactaristics:

1. They can thrive in tight, wild plantings.

2. They are disease and pest resistant.

3. They take well to coppicing, or hard pruning techniques where they are periodically cut back to the ground.

Traditional hedge management simplifies pruning and maintains health and productivity.

Major species will make up 50-60% of the multi-purpose edible hedge, and include hazelnut, hawthorn, blackthorn or bullaces, sea buckthorn or autumn olive if it is not invasive in your region. Note that European wild plums take to coppicing well, but according to USDA research American species of wild plums do not. Also note that there are some American species of hawthorns that take well to coppicing and are high quality edible fruits, which far surpass the European species. To maximize productivity, these major species should be spaced at essentially orchard spacings, approx 12-15' depending.

Support species should fill in the gaps between, still alternating heights when possible. My recommendations for these include: Asian pears, wild pears, rugosa roses, goumi, elderberry, medlar, currants, and brambles. Note that I do not include apples, European pears, or other common culinary fruits, as they are unlikely to be healthy and productive in such conditions. Occasionally I encounter an instance which excepts this rule, but in most cases, I would not expect them to do well in an edible hedge, and are more appropriate to other growing systems.

Finally, a great deal of additional plants can add to the productivity and biodiversity of the edible hedge, including:

For more information, ideas, and resources on hedgerow culture, visit our previous article on hedgerows

Resources

NOTE: in the following list, care should be taken to ensure that species are not invasive to your region, are appropriate to your specific sites and soils, and appropriate to "coppicing."

1. Suitable species for Australia, from a Permculture perspective: https://permaculture.com.au/venerating-and-regenerating-hedgerows/

2. Suitable species for humid tropical climates: https://steemit.com/permaculture/@reville/living-fences-in-indonesia-50-species-to-use-in-the-tropics

3. Hedgerow medicines: http://www.hedgerowmedicine.com/

4. Hedgerow foraging in UK, applicable to mant temperate climates, http://www.wildfooduk.com/hedgerow-food-guide/

Selected Citations (more research sources appear in text above)

1. Countour Hedgerows increase soil and water health in the tropics: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0167880995010122

2. Incease wildlife and biodiversity, UK: http://www.hedgelink.org.uk/index.php?page=21

2. Hedgerows reduce risk of food contamination: http://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=26370

3. Hedges reduce pests and increase pollination.http://calag.ucanr.edu/archive/?article=ca.2017a0020

4. Hedgerows and bocage in France: http://www.polebocage.fr/-Bocage-and-hedgerows-in-France,136-.html

5. Miyawaki technique effective in dry Mediterranean climates: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226157594_Effectiveness_of_the_Miyawaki_method_in_Mediterranean_forest_restoration_programs

reduction in pests, and increase in pollination. 1- 2 1/2'. 1- 2 1/2'.