- Geoff Lawton, The Permaculture Research Institute

RELATED VIDEO: Permaculture ideas for positive direct action!

Hot enough for ya? If not, just wait: According to NASA 2014, 2015, and 2016 were each consecutively the hottest years on record globally, and 2017 was the hottest year on record without an El Nino, coming in second after 2016. Already, 2018 is looking like it will be a contender.

This next couple of paragraphs are the bummer part, so first: LOOK! A BUNNY!

Of course, it would be nice if heat was the only problem. But no, the real problems caused by climate change will be ecosystem collapse, breakdown of the farming and food systems, increased disease and human health impacts, larger storms, more wildfires, potentially increased earthquakes and volcanic activity from ice melts, sea-level rise, refugee migrations caused by famine, drought, and flooding, and a whole host of secondary and tertiary affects that will be felt first and most profoundly by the globally disadvantaged. And, as researchers get a better picture of what our climate future will look like, they're increasingly predicting the most dire scenarios, unless bold dramatic action is taken immediately. Many researchers are now talking seriously of predictions of dire civilization-shaking consequences as early as 2030.

But for those of us who garden, we don't need NASA to tell us climate change is in full swing. In my biome of S.W. Michigan, an unusually brutal winter of temperature fluctuations between hot and cold left plants and ecologies reeling, then record flooding, followed by Spring starting a month late, and then going straight into more 90 degree days here than we typically average in a whole summer - and it's not yet June! Meanwhile, gardening and farming fora are filled with posts about increased pest problems, and scientific journals and extensions are noting climate-related spread of new pests each season. Others are widely reporting plagues of mosquitos and ticks. While it's hard to directly blame the whole of this on climate change, all of this is exactly the sort of thing predicted to result from climate change.

Meanwhile, political solutions don't seem forthcoming. The best chance we have is the Paris accord, which doesn't remotely go far enough to prevent the worst-case scenarios from still occurring, and places what even this environmentalist has to acknowledge are unrealistic and likely impossible burdens on the US.

However, there is good news. We each have the potential to respond in a way that is powerful and life-enhancing.

And there is still hope - if we stop waiting for politicians and start taking direct action.

While many poo poo the possibility of direct action, hoping instead to channel energy into their political candidate or cause, we know a few things for certain:

1. The consumer economy is driving the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change.

2. When the consumer economy falters, greenhouse gasses go down.

And 3, as "industry murdering" Millennials have proven time and time again, consumption choices are powerful and can have a direct effect on stunting and crashing corporations and industries.

And to the extent that it is itself sustainable, and it effects our spending and the spending of others, what we do in the garden can be a truly powerful, multi-pronged way to meaningfully address climate change.

As a mode of climate resistance, gardening offers two main benefits:

Resistance & Resilience

First, a garden offers us a meaningful way to act against climate change and the host of other negatives associated with "public/private" fascism. We'll start by talking about the mechanisms, then we'll get into the methods we can each use to make our home gardens, farms and public landscapes more effective tools in fighting climate change!

Resistance

1. Starve the beast. As stated above, the 1 million articles about Millenials killing industries proves that our consumer choices DO have a powerful impact. And Permaculture co-founder David Holmgren dug into the numbers to demonstrate that it is indeed possible to mitigate or even reverse climate change via consumption changes alone. But let's be clear, not every garden is a climate-fighting endeavor. Some gardens are demonstrably worse than driving a Hummer! The change we need to make to be effective is to replace consumption of corporate food and materials with those grown sustainably closer to home.

2. Reduce, reuse recycle. These are still powerful modes of reducing consumption and thus greenhouse gas emissions. Gardens give us a chance to do all three, through growing food, providing recreation at home, repurposing household items into garden-wares, and mulching and composting.

3. Protect wildlife habitat and biodiversity. One of the biggest problems with climate change is that it will further contribute to the ongoing mass extinction event underway. It's extremely powerful for us to use our landscapes to provide a sanctuary for wildlife, insects, and endangered plants. Again, not every garden does this. In fact, many gardens are war zones against biodiversity!

4, Sequestering carbon. A garden can be designed to actually directly fight climate change by sequestering carbon in the soil and in plant tissues.

5. Catching and infiltrating water. Another indirect effect of climate change is that it will contribute to further depleting our aquifers. While many gardens waste water for irrigation and fancy ornamental water features, gardens CAN be designed to catch water and get it back into the aquifer.

6. A garden CAN reduce our burden on the food system, which will be increasingly fragile as climate change continues.

7. Decrease suffering for as many as possible, and increase happiness for as many as possible, for as long as possible. Even if we can't stop climate change, we can use our gardens as a sanctuary habitat for humans and non-humans alike, and model for others how to better thrive in challenging times, because gardens can be important sources of resilience.

Resilience

1. Moderate climate around the home, providing cool in summer, warmth in the winter, and shelter in increasingly harsh storms.

2. Help us withstand shocks to the food and water system.

3. Provide recreation and stress relief during times of stress and disruption.

4. Help us to grow social capital and community cohesiveness.

Tips and Techniques:

But in these regards, not all gardens are created equal. In fact, some may actually achieve quite the opposite effect. So here are some tips and techniques we've used and recommend to make our gardens into powerhouses of climate change resistance and resilience:

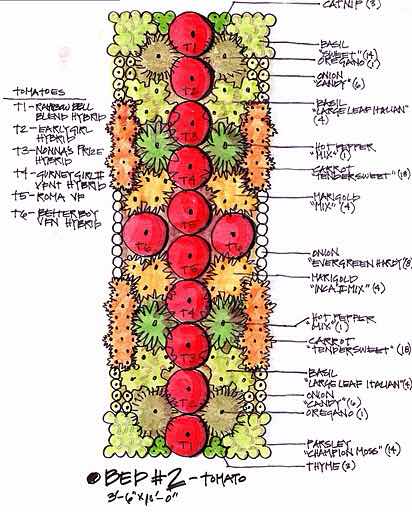

1. Grow food. Even in ornamental landscapes. Because our food system is arguably the #1 cause of climate change, and our traditional landscapes (especially lawns) are another major driver, using food plants to reform our landscape strikes to the core of climate change. While any garden that reduces lawn is likely a step in the right direction, and native plant gardens may provide increased biodiversity, a food garden reduces our consumption and reliance on the systems that are the leading cause of climate change. This does not necessarily mean having a traditional "food garden," which may actually deplete soil carbon, waste fertilizer and fossil fuels, and reduce biodiversity, but a well designed garden that integrates food plants can be especially powerful. Perennial edibles and no-till systems are two great ways to improve garden sustainability and performance. Perennial systems like edible hedgerows, edible prairies, coppices, and forest gardens may be the easiest and most climate-positive forms of garden we can grow. Every landscape should include some of these!

2. Grow fertility, healthy soil, and simultaneously sequester carbon. If we want to get serious about sequestering carbon, we need to have a plan to stop importing fertility and start growing it on site. When we import fertilizers, we're depleting non-renewable resources, and when we import compost, we're depleting carbon from someplace else, while adding to greenhouse gas pollution via shipping. Growing our own fertility ensures that we're actually sequestering carbon, reducing our overall greenhouse gas footprint, and our healthy soils will help take better care of our crops. A few key ways to grow fertility include: deep mulch gardening with home-grown mulch-maker plants, perennial fertility strips, edible hedgerows and other agroforestry systems, nitrogen fixing plants, and wetland or water gardens. Everyone should be composting, and some of the easiest methods for home-owners include sheet-composting, and trench composting, which do not require maintaining a pile or carting compost around the yard. Grow Bio-intensive is a method based on growing fertility using annual crops in the garden.

3. Grow some native plants. Native plants may provide better wildlife habitat and protect biodiversity, which research shows will increase the health of your garden and crop plants. This does not mean that your grandpa's daylilies or your aunt Petunia's petunias have to go, or that you've got to ditch the tomatoes. There's no proven benefit to growing ONLY native plants, but there are proven benefits to including them. In fact, because climates and soils have changed, in many regions "native" plants may be more difficult to grow in our modern non-native soils and climates, which may require measures that waste resources, pollute carbon and harm ecosystem biodiversity. Many native-only gardens also leave the human inhabitants reliant on the destructive food system. Meanwhile, some of the best native plants to grow are edible, and some of the best fruits and vegetables are natives! In my region, that includes paw paws, persimmons, currants, jersusalem artichokes, varieties of alliums, and many, many others.

4. Include wildlife habitat like rockeries, wood piles, unmown grasses, and messy garden areas. These will increase biodiversity, protect climate-threated wildlife, and attract beneficial organisms that help keep the garden healthy.

5. Have a design to catch and store the water on your site and use it wisely. Permaculture design is a great resources, since it starts with treating water as a "mainframe element" and teaches that we have an ethical obligation to constructively treat the water that falls on our properties. This also includes a plan for water-wise gardening, so that we can be responsible in how we use water, too. I recommend Toby Hemenway's 5-fold water wise gardening plan, as described in Gaia's Garden.

(Water designs at L.H.)

6. Use recycled materials in the garden whenever possible, instead of buying new.

7. Avoid manufactured concrete, cement, and faux brick landscaping products, as the concrete industry is one of the leading causes of carbon pollution, and shipping further contributes to the footprint. In fact, concrete is so unsustainable, that it needed its own number. Recycled concrete, or "urbanite," can be both aesthetically and ethically beautiful.

8. Avoid the use of plastic materials and plastic landscape fabrics. Not only do these contribute to climate change in their manufacture and shipping process, they also are quickly becoming the leading cause of plastic pollution of water and soil. Plastic in food production systems has been found to contaminate food at unhealthy levels.

9. Start exploring no-till gardening. This won't necessarily work for every crop, or every ornamental in every garden or landscape. However, there ARE plenty of crops that will actually grow better and with less labor and cost, when grown in no-till systems. You might not be able to replace the entire farm or garden with no-till right away, but you might be able to start saving time, and soil carbon, by figuring out how and where no-till will work for you.

10. Utilize the power of biodiversity, Biodiversity will increase the health and resilience of your plants, while also assisting wildlife and threatened plants. Having a variety of crops will mean you're protected against crop losses, pest issues and extreme weather events in a changing climate. Again, perennial edibles and perennial systems like hedgerows and forest gardens may be the superstars of a climate resilient garden, as they build up energy and store it over many years, and have deep roots to pump water, they may be less susceptible to all forms of extreme weather.

So, that is our checklist of tips and techniques to make the most of the climate-resistance garden. Am I missing anything? What steps are you taking? Leave a comment below, or share on social media by visiting us on Facebook.

------------------------------------

If you would like to learn more about climate resistance gardening, water harvesting, no-till gardening, growing fertility, perennial vegetables and growing systems, or see these techniques in action, consider joining us for this special event. We'll be offering this event twice this summer, on June 7th, from 2:30 pm - 5, and again on August 11th from 9:00am - noon.

Suggested donation: $20. @ Lillie House. To learn more or reserve your space, visit: https://squareup.com/store/lillie-house-permaculture/item/gardening-against-climate-change-intro-to-permaculture